“The greatest, most beautiful thing is compassion expressed through music” – Savithri Rajan

Excerpt from: Tyagaraja and the Renewal of Tradition: Translations and Reflections by William Jackson (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidas, 1994), pp. 174-175

https://search.worldcat.org/en/title/878687716

How does Savithri Rajan perceive Tyagaraja? She characterizes Tyagaraja as an heroic soul who was able to reach out through shared feelings and colloquial idiom to ordinary people; he was willing to serve selflessly like a mother risking her own life to jump into a pool and save a drowning child. Yet she feels that Tyagaraja simultaneously holds to the tradition of communicating the greatest message of the Upanisads. To her, this is an important point, “Because to Hindus the Upanisads together form the core of the Hindu religion; the ultimate, the last word in philosophy, the Upanisads lead one to a transcendental silence,” which is found in the lives of the Buddha, Sankara, and Ramana Maharshi. Savithri Rajan believes that Tyagaraja, like these other great men, was always meditating, but his medium of expression was nādam, “sound” – he was an aspirant who followed nādopāsana, the approach or worship by way of sound. She points out that Tyagaraja composed a song beginning with the word nādopāsana saying there is nothing higher than worship via sound, music is the best vehicle because Brahman is nādam – divine sound – which is the omnipresent, omniscient power, “call it Power with a capital ‘P’, call it God, call it Christ, call it Krsna, call it Rāma.”

What was it that Tyagaraja was expressing in his songs? Savithri Rajan believes that everything Tyagaraja felt in his search to understand and have compassion was experienced and expressed through the medium and vehicle of music. In her view, “the greatest, most beautiful thing is compassion, karuna, the ability to feel for others.” And every song of Tyagaraja has “karunā sāgara” – an ocean of compassion in it.

“The music of Tyagaraja’s compositions can be so poignant I have seen people with eyes wet when listening to a great piece rendered by a great vidvān [a very learned performer]. To one who does not understand Telugu and does not know the rāga, but is nevertheless moved by the piece and feels the sentiment and emotion in it, the communication is through the nādam – and there are many such people.”

The reason there are many is that the communication of realizations occurs at a deep level utilizing notes and rhythms best able emotionally to move South Indians of various backgrounds: the unsophisticated, the temple-anchored faithful, the festival-goers who express inner spiritual urges through participation in music and pageantry. These various South Indians feel a serious lack if a Tyagaraja song is not part of any musical or religious program. […]

Savithri Rajan feels that today’s performing musician “owes everything” to Tyagaraja. “What is his concert worth if he cannot render an Ayyarval kirtanai [song by Tyagaraja] well? His merit and reputation are judged by this touchstone.” Further, she recalls, that her mother, who had “unerring bhakti” held that the music-charged words of Tyagaraja in honour of Rama constitute a talisman with special power.

As Savithri Rajan sees it, the listener, the performer, the housewife, the spiritual seeker, and various kinds of students, – each in a different way approaches Tagaraja and his multifaceted personality, which he pases on to others, his simplicity, renunciation and sensitivity to the onslaughts of materialism and human frailty, all made this “emaciated, fragile man, a mendicant by choice, a seer, a sage, and a saint by the grace of Rama,” and thus he stands out as an inspiration to all.

She believes that in the fast pace of the modern world Tyagaraja’s bhakti message of music and love of God and man is of great value, and that it influences many who have the ear to hear and leisure to meditate. She recalls that her teacher, Tiger Varadachariar used to say that Tyagaraja brought Valmiki’s Rama closer, “adorably closer,” and in a moment of great appreciative experience he would even declare that Tyagaraja’s Rama was greater than Valmiki’s Rama. “Tyagaraja talks to his Rama, praises, cajoles, and even quarrels with Rama.” She feels that the aesthetic experience is heightened by this intimaciy. She feels that the depictions of Tyagaraja’s yearning have elevated and ennobled her thoughts and helped her to keep equanimity in various situations in her life, and she believes many others born in her culture have had similar experiences. […]

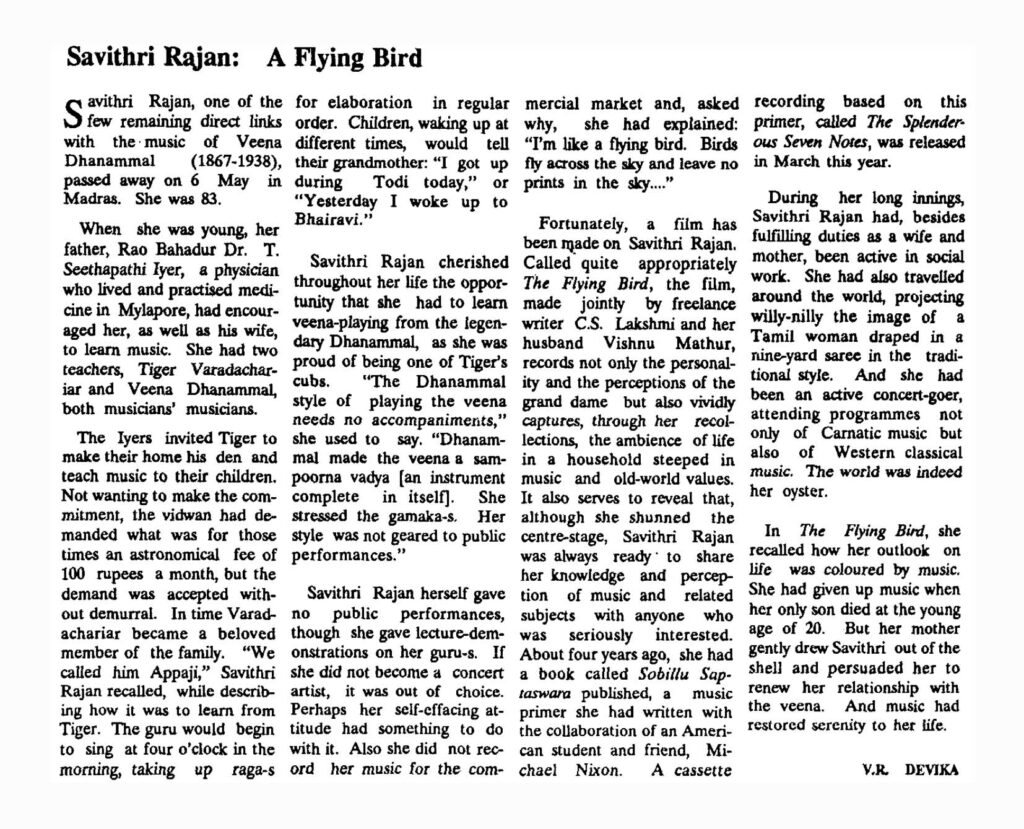

In her private LP recording titled “Dedication to her guru, Veena Dhanammal”, Savithri Rajan (1908-91) pays tribute Veena Dhanammal (1867-1937). As a child she was tutored by the legendary singer and composer known as “Tiger” Varadachariar (1876-1950, a disciple of Pattanam Subrahmanya Ayyar).

Veena Dhanammal is a legend

Veena Dhanammal is a legend; she was one in her own lifetime. Was she for real? There’s so little of her music which has survived and even loss which is heard, and yet her music has been praised in such superlative terms by those privileged to have listened to her. – Sruti Magazine >>

Item list with composers and research link

Intacalamu (varnam) – Begada – Adi – Tiruvotriyur Tyagaiyer

Ninuvinagati gana – Kalyani (alapana) – Adi – Subbaraya Sastri

Sri Raghuvara sugunalaya – Bhairavi – Adi – Tyagaraja

Nicittamu na bagya – Vijayavasanta – Adi – Tyagaraja

Tanam – Ghanaraga panchakam (order: Nata, Gaula, Arabhi, Sri, Varali)

Maname bhushanamu – Sankarabharanam – Misra capu – Govindaswami Ayya

Mariyada teliyakane (javali) – Surati – Rupaka – Patnam Subrahmanya Iyer

Find song lyrics and information about Carnatic ragas including those by the above composers >>

(e.g. type “Tyagaraja rare ragas” or “javali by Patnam Subrahmanya Iyer”)

Tips: (1) to automatically play both the sides of the LP-recording, click the play button; (2) scroll down to access the remaining tracks; (3) download the audio files, liner notes and images here: https://archive.org/details/savithri-rajan-LP-record-dedication-guru-veena-dhanammal

(4) Please be patient if the page takes a little longer to load (depending on available bandwidth)

Tips: in the above search field, type a combination of names and subjects of special interest: to find more audio and video contents sung or played by a favourite musician or musical instrument; along with preferred raga or tala, on the occasion of a festival or lecture demonstration item (e.g. varnam, kriti, tillana), institution (e.g. Music Academy Madras, Narada Gana Sabha), place (e.g. Chennai, Hyderabad, Kerala), or current issues (e.g. titles and awards like Sangita Kalanidhi, women performers, caste) | How “Safe search” is used on this website >>