“Please note that Internet Archive services will have limited availability as we continue maintenance. […] We stand with all libraries that have faced similar attacks—British Library, Seattle Public Library, Toronto Public Library, and Calgary Public Library—and with the communities we serve. Thank you for standing with the Internet Archive as we continue to fight back on behalf of all affected readers.” | Updates: Internet Archive Blogs >>

Category archives: Research

“Bhava” and “Rasa” explained by V. Premalatha

“Rasa is realised in from the combination of the sthāyibhāva (permanent and dominant emotional mood) with the vibhāva-s (the objects of emotions such as the hero and the heroine, and the exciting causes such as the spring, flowers, moonlight and the bower), anubhāva-s (the external manifestations of emotions such as the movement of the eye-brows, glances and smile) and the vyabhicāribhāva-s (accessory moods) which come and go helping in the manifestation of the rasa). Bharata mentions eight dominant emotional moods, or sthāyibāva-s, that may be aroused by a dramatic representation into the state of aesthetic pleasure. These are rati (love), hāsa (laughter), śōka (sorrow), krōdha (anger), utsāha (energy), bhaya (fear), jugupsā (repugnance) and vismaya (wonder); the rasa-s corresponding to these are respectively called śṛṅgāra, hāsya, karuṇa, raudra, vīra, bhayānaka, bībatsa and adbhuta. Later writers accept a nineth rasa called śānta corresponding to the sthāyibāva of nirvēda (detachment). Really the rasa or the aesthetic pleasure derived from literature is one and the same in all cases; the division into various rasa-s is based on the difference in the sthāyibāva-s which contribute to the rasa- s. This rasa is a condition produced in the spectator, is a single feeling and a pleasurable one”. (p.286- 287 Indian Theories of Meaning, by K Kunjunni Raja)

Dr. V Premalatha, Department of Music, Central University of Tamil Nadu, Thiruvarur , “Rasa and Kāla of Rāgas, by V Premalatha,” MusicResearchLibrary, accessed October 22, 2024, http://musicresearchlibrary.net/omeka/items/show/2287.

Tip: find more in-depth studies here: http://musicresearchlibrary.net >>

“Music Research Library is a collection of publicly accessible and downloadable electronic resources related to Indian Music organized into various collections. These include manuscripts, articles, books, periodicals, source texts and teaching resources.”

Beyond performing competence: Students set to become good teachers and informed citizens as well

By S. Sankaranarayanan in Sruti (1998) | Excerpts that remain relevant today:

Observations on the teaching of music at the Rotterdam Conservatory, Holland:

Along with theory and history of music, the students [at the Rotterdam Conservatory] also acquire knowledge of ancillary aspects such as voice modulation and the reading and writing of notation. However, weightage is given to performing competence. […] As a means of widening their musical horizons, the students are encouraged to have exposure to other systems of music as well. […] Training in teaching methods is also imparted to the students so that they can become good teachers.

Along with music, the students are given a wide ranging and comprehensive liberal education so that, at the end of the course, they become not only competent musicians and/or teachers but informed citizens as well.

Dr. Suvarnalata Rao, Research Scientist at the National Centre for the Performing Arts (Mumbai)

Role of Research in Music Education

The lakshya sampradaya of music which is passed from guru to sishya gets altered when music is performed in a recital. This happens because of the elements of ‘entertainment’, such as indulgence in virtuosity or novelty for its own sake, and playing to the gallery. Because many performers also happen to be teachers, such changes, subtle and not so subtle, that creep into the recitals also influence the teaching, including the course content of contemporary music education. Only a researcher can observe and point out such deviations to the artists, as no performer can be his own critic unless he has a bent for research which is rather rare. It is for the practitioners either to accept or not to accept the researcher’s findings. However, to be effective, a researcher (and for that matter, a musicologist or critic too) should be be able to perform, though not necessarily as a concert performer; otherwise his opinion would carry little weight.

[Commentary by S. Sankaranarayanan: It should, however, be remembered that, firstly, theory is not an unalterable entity and, secondly, theory itself is a codification of practices, though quite often it is one generation behind the latter. Fortunately, music has an admirable tradition of accomodating change].

Dr. N. Ramanathan, [former] Head of the Department of Indian Music at the University of Madras

Read the full report: https://sruti.com/articles/spotlight/teaching-of-indian-music >>

What of the future? New electronic gadgets produce “mind-blowing” noises in the name of music, and there is a new breed of tunesmiths and song mongers. All this will however be a temporary aberration. People like Semmangudi have ensured this.

G. Dwarakanath in “Setting high standards of purity” (Folio Music November 29, 1998) | PDF-Repository >>

“Children should grow with joy, courage and freedom and a discipline born out of these attributes. The fundamental principle is joy, suggestion must be the method, the emphasis should be on the imaginative and creative experience of music and teaching should follow a “flow-form-flow” spiral.

VV Sadagopan was clearly in favour of lakshya (aesthetic perception) over lakshana (intellectual abstraction) at school, college or university.” – T.K. Venkatasubramanian in “VV Sadagopan – An educator with a mission”, Sruti Magazine >>

More resources | Disclaimer >>

What’s the difference between Hindustani and Carnatic music?

At first, this question seems easy to answer: just watch performers from either strand of Indian music and you’ll know Which is Which, merely going by the instruments in use, or how they dress and watching the body language involved: harmonium or sarangi vs. violin for melodic accompaniment for most vocal recitals, and tabla drums rather than a double-faced mridangam.1

“Even at the peak of her career M.S.Subbulakshmi continued to

learn from other musicians” – R.K. Shriram Kumar >>

Tambura posture, fingering & therapeutic effect >>

Even in the absence of other clues, experienced listeners know what distinguishes one concert item from another, in order to immerse themselves in that which endows “classically trained” musicians across South Asia with a deeply felt sense of unity: raga, aptly defined as a “tonal framework for composition and improvisation” by Joep Bor in The Raga Guide.

What binds Hindustani and Carnatic music lovers together is the experience of raga which, given its roots (lit. colour, beauty, pleasure, passion), denotes a cultural phenomenon rather than just a particular combination of notes. This means that raga-based music is more widely shared than one would expect in the modern world due to its capacity to transcend linguistic boundaries. In short, both strands of Indian music, Hindustani and Carnatic music, have absorbed a wide range of regional traditions throughout history. At the same time, “raga music” continues to serve as a vehicle for meaningful lyrics in any conceivable genre in addition to “classical” or “devotional” music. Even when rendered by an instrumentalist or sung without lyrics (as customarily done within both Hindustani and Carnatic recitals) each raga constitutes “a dynamic musical entity with a unique form, embodying a unique musical idea”. […] As regards Hindustani ragas, they “are known to musicians primarily through traditional compositions in genres such as dhrupad, dhamar, kyal, tappa, tarana and thumri. Good compositions possess a grandeur that unmistakably unveil the distinctive features and beauty of the raga as the composer conceived it.” (Joep Bor).

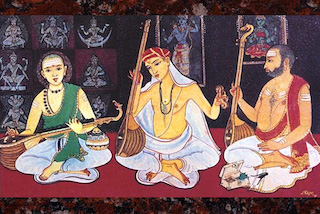

the composers most revered and performed by Carnatic musicians

Muttusvami Dikshitar

Sri Tyagaraja

Syama Sastri

Painting by S. Rajam © Sruti Magazine >>

Composers on DhvaniOhio >>

A comparable range of genres is available to Carnatic musicians, including varnam, kirtana, kriti, ragam-tanam-pallavi, padam, javali, tillana with a notable difference: since the 16th century, Carnatic compositions take up more time in order to render the lyrics faithfully, as intended by their composers and jealously guarded by teachers, discerning listeners and critics alike.

It is hard to imagine how such ideas would have worked before the advent of the tambura or tanpura – another feature of Indian music which may explain why older scales and theories have fallen into oblivion ever since – in spite of frequent mentions in text books.

But it’s harder to explain the musical differences in plain language while listening attentively as their respective performances unfold: differences begin to multiply, mostly in ways too subtle for words. Such differences call for probing into the depths of Indian “classical” music in the sense of a particular branch of music that is governed by clearly defined rules as well as unwritten conventions valued by professionals and connoisseurs.

For Indian listeners, such distinctions are mostly associated with a particular region, like the northern Hindustani and southern Carnatic music even if deceptive when it comes to the birth places of noted Hindustani exponents: many famous musicians were born or trained in Bengal in the east, and Dharwad in the south, also known as “Hindustani music’s southern home“. Being associated with a famous regional tradition or lineage is mentioned in most programme notes, like the vocal gharana known as the “Dharwad Gharana” or “Gwalior Gharana” in Hindustani music; and likewise, southern musicians pride themselves for having learned their arts within a bani (“family tradition”) designated by a particular town, for instance Tanjavur (vocal), Lalgudi (violin) and Karaikudi (vina or veena).

Then there are the preferred languages used in song lyrics in the case of vocal music; and certain rhythmic patterns local listeners would instantly feel familiar with or, conversely, associate with “novelty” when first employed beyond their place of origin. The latter is eagerly anticipated toward the end of a recital. In the opening and main parts of a recital, the most obvious differences between Hindustani and Carnatic music include the following traits:

Art © Arun V.C.

- Hindustani musicians prefer “accelerating” almost imperceptibly – from slow to fast tempo – during an alap (raga alapana, the melodic improvisation preceding a composed theme); this preference entails presenting fewer items compared to their Carnatic peers;

- many (though not all) adhere to the convention of associating rāgas with a specific time of the day, or a particular season ;2

- by contrast, a typical Carnatic or Karnatak concert opens with two or three items in a brisk tempo, including sections in “double tempo”, before elaborating a particular raga in a slow-to-fast format akin to the Hindustani format known as “imagination” (khyal or khayal) traceable to 18th c. court music;

- Carnatic recitals are enriched by arithmetic elements derived from the repertoires of temple and dance musicians, and coordinated by visible gestures (something listeners love to emulate for the sake of self-immersion or as a sign of appreciation); and not surprisingly, rhythmic intricacies were successfully adopted and refined as part of Hindustani tihai patterns, most successfully by Ravi Shankar in the course of collaborations with southern instrumentalists (duly acknowledged in Raga Mala: The Autobiography of Ravi Shankar); be it for his solo sitar recitals or novel, mostly temporary jugalbandi ensembles like the one documented on video: recorded in 1974 at the Royal Albert Hall in London: “As far back as 1945, I was absorbing the essence of these from the fixed calculative systems of the Carnatic system.” (To understand their application, watch a tarana on YouTube repeatedly, starting from 3:27) Unsurprisingly this process of give-and-take, once proven successful, has become too common to bother crediting it to any particular source, other than declaring it a “shared heritage” cherished by musicians and audiences all over the world: Unity in Diversity at its very best!

To appreciate some of the aforementioned characteristics in the context of South Indian music, listen to recitals by two of its most beloved exponents:

From the above mentioned differences follows the most important one, namely the amount of time assigned to compositions based on elaborate lyrics: the concise bandish in a Hindustani recital vs. the tripartite kriti several of which occupy pride of place in Carnatic music.

The standard syllabus for South Indian “classical” music is ascribed to 16th c. composer Purandara Dasa of Vijayanagar (modern Hampi in northern Karnataka as indicated on the music map seen below). His method proved so efficient as to provide a common ground for aspiring singers or instrumentalists from many regions and linguistic backgrounds. This may explain how such music invites the convergence of several voices or instruments into one (unison): a soloist accompanied by violin just as two vocalists (popular duos known as “Brothers” and “Sisters”), or pairs of flutes, lutes (vina) and violinists, all capable of achieving perfect alignment at any given moment during a recital; and this not merely for evenly paced motifs but with equal ease in richly embellished passages. For good measure, such feats require neither notation nor lengthy rehearsals but instead combine musical memory with considerable freedom to enrich predictable patterns with one’s own flights of imagination.

As regards inevitable specialization such as a particular vocal or instrumental style, required for mastering certain melodic and rhythmic intricacies and compositions, there is an infinite variety to delve into: variety that explains the evolution of two great music “systems” that kept evolving and intersecting ever since musicologists became obsessed with classifying and validating certain features in the 19th and 20th centuries.

For non-Indian music lovers and students, Yehudi Menuhin’s reminiscences titled “Unfinished Journey” may be a good starting point: the violin virtuoso was among the first to appreciate fact that “Indian musicians are sensitive to the smallest microtonal deviations, subdivisions of tones which the violin can find but which are outside the crude simplifications of the piano (or harmonium)”. His interest in Indian violin music motivated Menuhin to invite the South Indian violin virtuoso Lalgudi Jayaraman to tour the UK and participate in the 1965 Edinburgh music festival.

For a better understanding of what Yehudi Menuhin meant by “smallest microtonal deviations”, listen to the very first composition most learners of Carnatic music have learned – a gitam (didactic song) by Purandara Dasa – in: A brief introduction to Carnatic music >>

“The classical music of the West has influenced

our musical culture” – Manohar Parnerkar in

Sruti Magazine August 2019 >>

Since then, musicians from various backgrounds have never ceased to contribute to an unprecedented intercultural dialogue: exponents of western classical, ecclesiastical and minimal music just as jazz, pop and film music, all set to explore new horizons together with their Indian peers.

Tips

- to explore the above topics on your own, refer the Indian sources recommended here >>

- in order to get a clear idea what this means in practice, listen closely to audio and video contents featuring two prominent families of violinists whose roots lie in South India: one known as the Parur bani (brothers M.S. Gopalakrishnan & M.S. Anantharaman), and the other brought into prominence by N. Rajam (Hindustani violin) and her brother T.N. Krishnan (Carnatic violin)

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Michael Zarky (Tuning Meister) for providing valuable tips and corrections for this post and previous Carnaticstudent courses including those offered in conjunction with university eLearning programmes.

More about the above person(s) and topics

Periodicals and sites included | More resources | Disclaimer >>

Photo © Ludwig Pesch

Learn & practice more

- A brief introduction to Carnatic music (with music examples and interactive map)

- Bhava and Rasa explained by V. Premalatha

- Free “flow” exercises on this website

- Glossary (PDF)

- Introduction (values in the light of modernity)

- Video | Keeping tala with hand gestures: Adi (8 beats) & Misra chapu (7 beats)

- Voice culture and singing

- Why Carnatic Music Matters More Than Ever

- Worldcat.org book and journal search (including Open Access)

- “The music of the Indian subcontinent is usually divided into two major traditions of classical music: Hindustani music of North India and Karnatak music of South India, although many regions of India also have their own musical traditions that are independent of these. […] In fact, many of these instruments are often used in both North and South India, and there are many clear relationships between the instruments of both regions. Furthermore, often instruments that are slightly different in construction will be identified by the same name in both the south and the north, though they might be used differently.” | Read the full essay “Musical Instruments of the Indian Subcontinent” by Allen Roda published by the Metropolitan Museum (New York) >> [↩]

- Noted musicologist V. Premalatha comes to the conclusion that as an “extra-musical factor”, association of time with rāga “survives very strongly in the North Indian system of music and has not affected the South Indian Music“. [↩]

Indian music studied from a social and intercultural perspective

Ethnomusicology can be considered as the holistic and cultural study of music existing in various folk, tribal and other ethnic societies.

Details

Ethnomusicology can be considered as the holistic and cultural study of music existing in various folk, tribal and other ethnic societies. The discipline ethnomusicology deals with the study of music from a social and cultural perspective and aims to survey and analyze the music traditions of various cultures. Ethnomusicology also emphasizes the study of music of one’s own and other cultures which promotes the intercultural perspective of music. Initially, the Indo-British interrelationship paved the way for intercultural communication through musical works and set the foundation for ethno musicological study in India. Ethnomusicology emerged in India during the British period when western authors started to write about Indian music in English language mainly for western readerships. Intercultural aspects can be found in all styles of music because of the cultural changes in societies that are induced by the changing reigns of rulers in the different ages of a nation‟s history. […]

After the 1980s, concepts of anthropology and musicology merged and more emphasis was placed on the observation of the process of musical creation, as seen in improvisations and performances. The focus of the study has shifted towards making critical examinations, rather than collecting abstract information. […]

Source: “Emergence of Ethnomusicology As Traced in Indian Perspectives” by Bisakha Goswami (Assistant Professor in Musicology, Rabindra Bharati University)

URL: https://www.academia.edu/10205543/Eemergence_of_Ethnomusicology_As_Traced_in_Indian_Perspectives

Date Visited: 8 September 2023

Classical music is the most refined and sophisticated music to be found in the subcontinent of India. There are many other forms, however, which have a specific function in the society, and these are by no means devoid of artistic expression. The great diversity of music in India is a direct manifestation of the diversity and fragmentation of the population in terms of race, religion, language, and other aspects of culture. The process of acculturation, so accelerated in modern times, is still not a very significant factor in many areas of the country. There remain remote pockets where tribal societies continue to live much as they have done for centuries.

“Tribal, Folk and Devotional Music” by NA [Nazir Ali] Jairazbhoy in AL Basham (ed.). A Cultural History of India. London: Oxford University Press, 1975, pp. 234-237.

There is a need for intercultural education. We all need to work together to bridge these divides not only between religions and castes but also regions. It is not correct to think that one part is better than the other. Some of the limitations of India as a whole are due to our common heritage, say the one that has restricted women from having a flourishing life for themselves.

Source: Prof. V. Santhakumar (Azim Premji University) in “On the so called North-South Divide in India” | Read the full blogpost: Economics in Action (13 April 2024) >>

Some clarifications on caste-related issues by reputed scholars

Understanding “caste” in the context of Indian democracy: The “Poona Pact of 1932”

“Mahatma Gandhi and BR Ambedkar differed over how to address caste inequities through the electoral system. Their exchanges led to the Poona Pact of 1932, which shaped the reservation system in India’s electoral politics. […]

Two prominent figures who have significantly contributed to this discourse are Mahatma Gandhi, Father of the Nation, and Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar, Father of the Constitution. The two stalwarts of Indian politics, while revered equally by the public, had contrasting views on the caste system. Their subsequent debates have shaped the course of Indian society and politics. While Gandhi denounced untouchability, he did not condemn the varna system, a social hierarchy based on occupation, for most of his life. He believed in reforming the caste system through the abolition of untouchability and by giving equal status to each occupation. On the other hand, BR Ambedkar, a Dalit himself, argued that the caste system disorganised and ‘demoralised Hindu society, reducing it to a collection of castes’. […]

And yet, despite their differences, they developed an understanding to work for the betterment of the marginalised.” – Rishabh Sharma in “How Ambedkar and Gandhi’s contrasting views paved way for caste reservation” (India Today, 6 October 2023)

URL: https://www.indiatoday.in/history-of-it/story/ambedkar-gandhi-caste-system-poona-pact-1932-reservation-2445208-2023-10-06

~ ~ ~

“That upper caste groups should declare themselves to be OBCs [Other Backward Castes] and want to avail of the reservation policy is a pandering to caste politics of course, as also are caste vote-banks. It is partially a reflection of the insecurity that the neo-liberal market economy has created among the middle-class. Opportunities are limited, jobs are scarce and so far ‘development’ remains a slogan. There’s a lot that is being done to keep caste going in spite of saying that we are trying to erode caste. We are, of course, dodging the real issue. It’s true that there has been a great deal of exploitation of Dalit groups and OBC’s in past history; making amends or even just claiming that we are a democracy based on social justice demands far more than just reservations. The solution lies in changing the quality of life of half the Indian population by giving them their right to food, water, education, health care, employment, and social justice. This, no government so far has been willing to do, because it means a radical change in governance and its priorities.” – Romila Thapar (Emeritus Professor of History, Jawaharlal Nehru University) interviewed by Nikhil Pandhi (Caravan Magazine, 7 October 2015)

URL: https://caravanmagazine.in/vantage/discipline-notion-particular-government-interview-romila-thapar

~ ~ ~

“Casteism is the investment in keeping the hierarchy as it is in order to maintain your own ranking, advantage, privilege, or to elevate yourself above others or keep others beneath you …. For this reason, many people—including those we might see as good and kind people—could be casteist, meaning invested in keeping the hierarchy as it is or content to do nothing to change it, but not racist in the classical sense, not active and openly hateful of this or that group.” – Book review by Dilip Mandal for Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents (The Print, 23 August 2020)

URL: https://theprint.in/opinion/oprah-winfrey-wilkerson-caste-100-us-ceos-indians-wont-talk-about-it/487143/

~ ~ ~

“The theoretical debate on caste among social scientists has receded into the background in recent years. [However] caste is in no sense disappearing: indeed, the present wave of neo-liberal policies in India, with privatisation of enterprises and education, has strengthened the importance of caste ties, as selection to posts and educational institutions is less based on merit through examinations, and increasingly on social contact as also on corruption. There is a tendency to assume that caste is as old as Indian civilization itself, but this assumption does not fit our historical knowledge. To be precise, however, we must distinguish between social stratification in general and caste as a specific form. […]

From the early modern period till today, then, caste has been an intrinsic feature of Indian society. It has been common to refer to this as the ‘caste system’. But it is debatable whether the term ‘system’ is appropriate here, unless we simply take for granted that any society is a ‘social system’. First, and this is quite clear when we look at the history of distinct castes, the ‘system’ and the place various groups occupy within it have been constantly changing. Second, no hierarchical order of castes has ever been universally accepted […] but what is certain is that there is no consensus on a single hierarchical order.” – Harald Tambs-Lyche (Professor Emeritus, Université de Picardie, Amiens) in “Caste: History and the Present” (Academia Letters, Article 1311, 2021), pp. 1-2

URL: https://www.academia.edu/49963457

~ ~ ~

“There is a need for intercultural education. We all need to work together to bridge these divides not only between religions and castes but also regions. It is not correct to think that one part is better than the other. Some of the limitations of India as a whole are due to our common heritage, say the one that has restricted women from having a flourishing life for themselves.” – Prof. V. Santhakumar (Azim Premji University) in “On the so called North-South Divide in India” (personal blog post in Economics in Action, 13 April 2024)

URL: https://vsanthakumar.wordpress.com/2024/04/13/on-the-so-called-north-south-divide-in-india/

There is a continuing association of apsaras with heroes, as for instance in the hero-stones of later times, which show the hero being taken up to heaven by apsaras arter he has died in battle. There is also an association with heavenly musicians, the Gandharvas. In the epic version, the identity of Sakuntala as an apsara is reiterated by the small details which [unlike those found in Kalidasa’s portrayal] make her different from an ordinary woman.

Details

The apsara was a beautiful woman made for dalliance, the fantasy woman of the world of the heroes. In later times the apsaras fade when the goddesses become prominent. The apsaras are not, therefore, the same as women of the earth, they have their own order and their own codes of behaviour and authority. In a sense they are a counterweight to the insistence on the pativrata as the ideal woman – the life-long, devoted, self-effacing wife to her husband – and to that extent alleviate the dreariness of the didactic sections of the epic [Mahabharata] with their heavy male-dominated pronouncements.

There is a continuing association of apsaras with heroes, as for instance in the hero-stones of later times, which show the hero being taken up to heaven by apsaras after he has died in battle. There is also an association with heavenly musicians, the Gandharvas. In the epic version, the identity of Sakuntala as an apsara is reiterated by the small details which [unlike those found in Kalidasa’s portrayal] make her different from an ordinary woman.

Yet she is in the mould of the other epic heroines – Draupadi, Kunti, Gandhari – strong women who as mothers and wives dominate the story and whose individuality cannot be overlooked. Epic heroines are sometimes associated with the knowledge of a treasure which the hero seeks, or else they protect the treasure. In the narrative of Sakuntala the treasure may be symbolised by the son she brings to the hero, a son who was to be unique in the lineage of the Purus. The eulogies on Bharata in the later tradition, exalting him as the ancestor of a famous clan (even though his children died and he was succeeded by an adopted son); marking him out as a major figure in the lineage not only requires introduction through an unusual birth – namely, a three-year gestation with a mother who could be either an apsara or a forest dwelling woman – it also ensures that the story of Sakuntala remains in the consciousness of those who live in the land of Bharata.

Source: Romila Thapar in “The Narrative from the Mahabharata”, Sakuntala: Texts, Readings, Histories (New Delhi 1999), pp. 41-42

Article 52 of the Constitution says, “There shall be a President of India,” with no mention of Bharat. […] India is already called Bharatam in Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, and Malayalam.

Source: livemint.com (5 September 2023)

[Bold typeface added above for emphasis]

Tips: in the above search field, type a combination of names and subjects of special interest: to find more audio and video contents sung or played by a favourite musician or musical instrument; along with preferred raga or tala, on the occasion of a festival or lecture demonstration item (e.g. varnam, kriti, tillana), institution (e.g. Music Academy Madras, Narada Gana Sabha), place (e.g. Chennai, Hyderabad, Kerala), or current issues (e.g. titles and awards like Sangita Kalanidhi, women performers, caste) | How “Safe search” is used on this website >>