Find song lyrics (composers) & translations for these and other ragas >>

Download this audio file (2 MB, 2 min. mono)

Credit: eSWAR / FS-3C Sruthi petti + Tanjore Tambura

J.A. Jayant (YouTube Channel):

Gaayathi Vanamali by Sadasiva Brahmendra in Adi tala

Listen to a Varnam sung by Bhushany Kalyanaraman >>

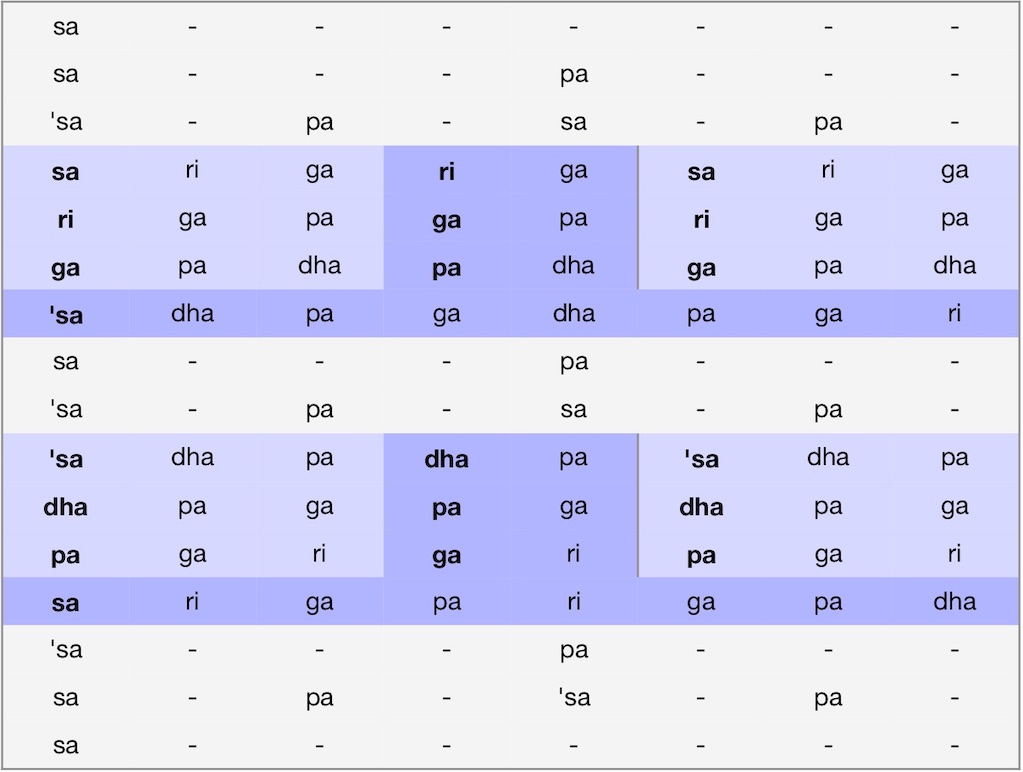

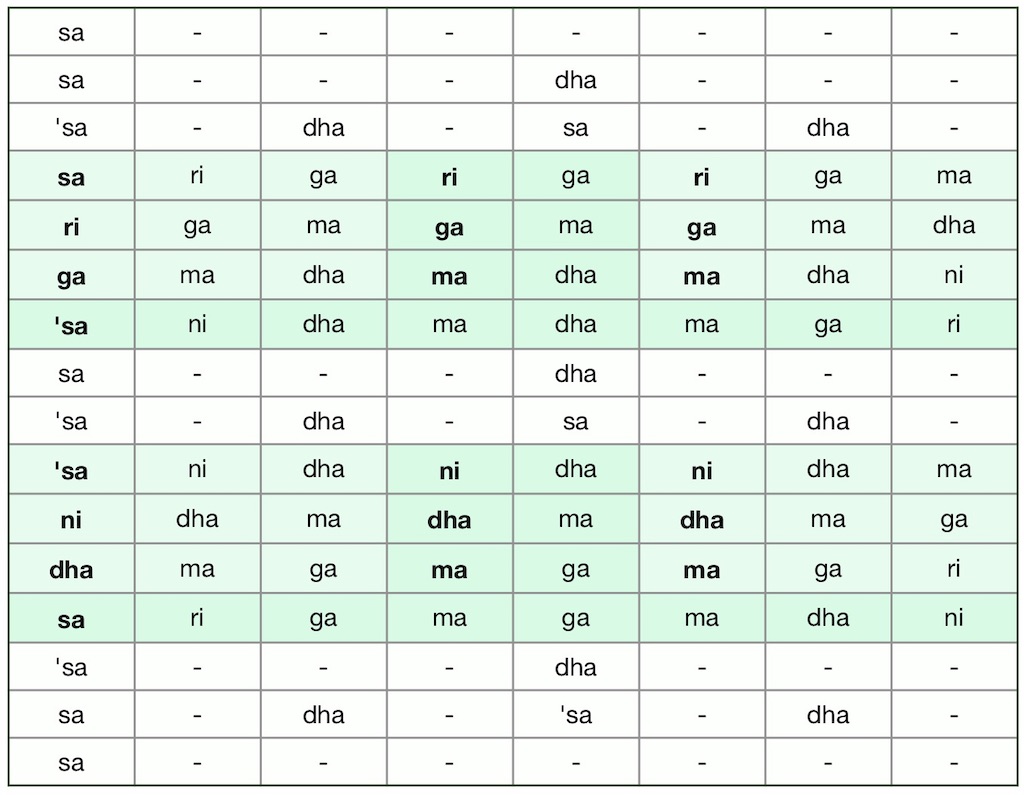

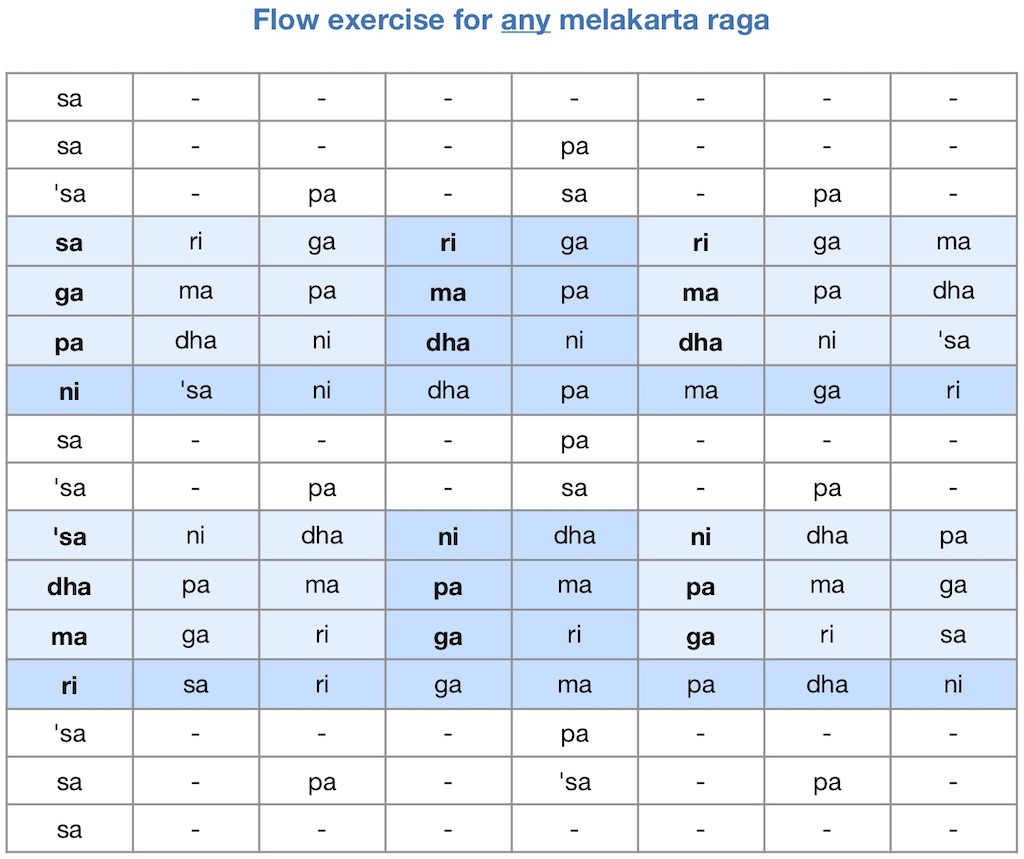

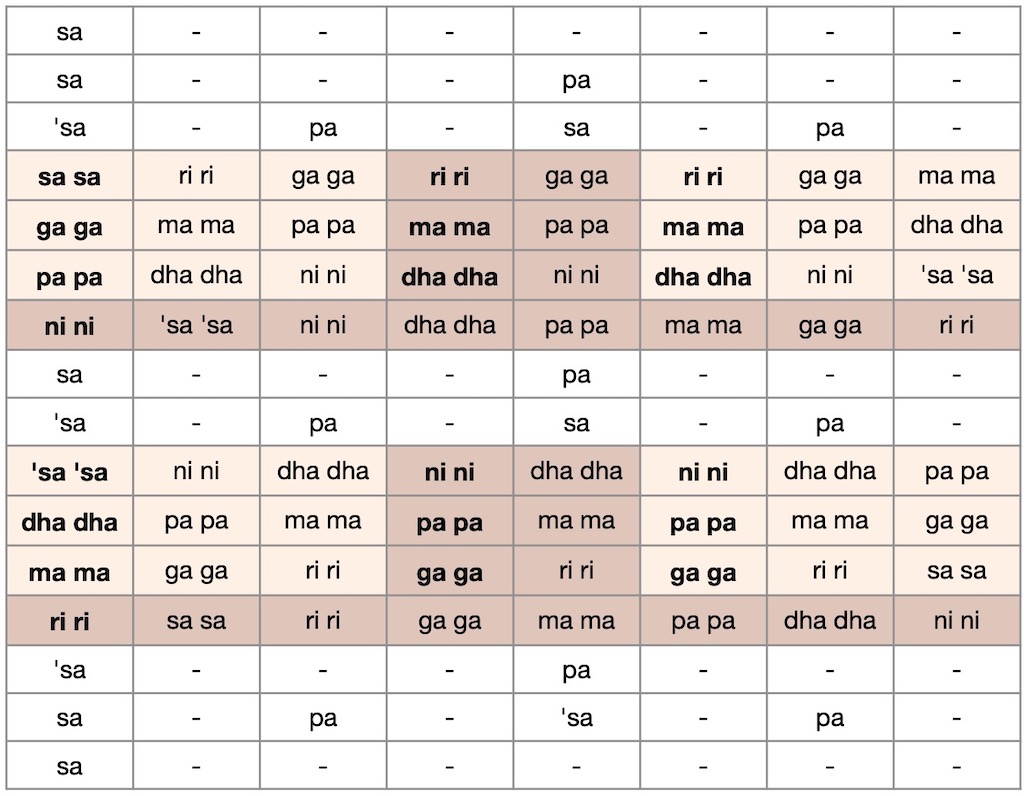

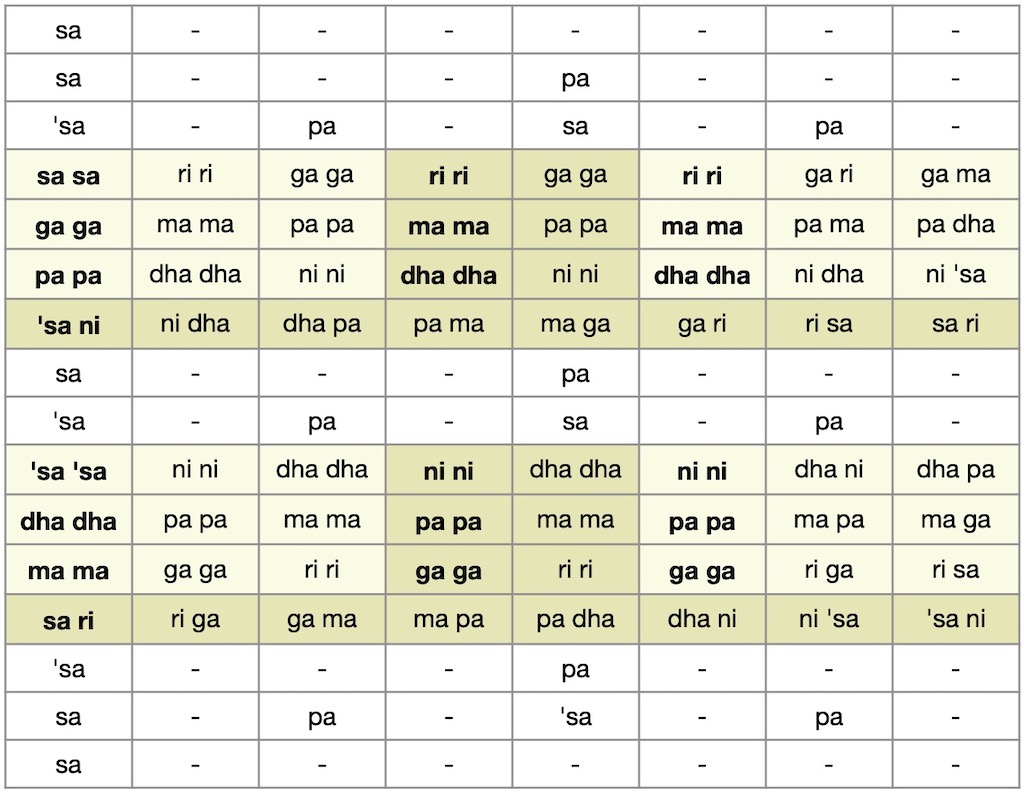

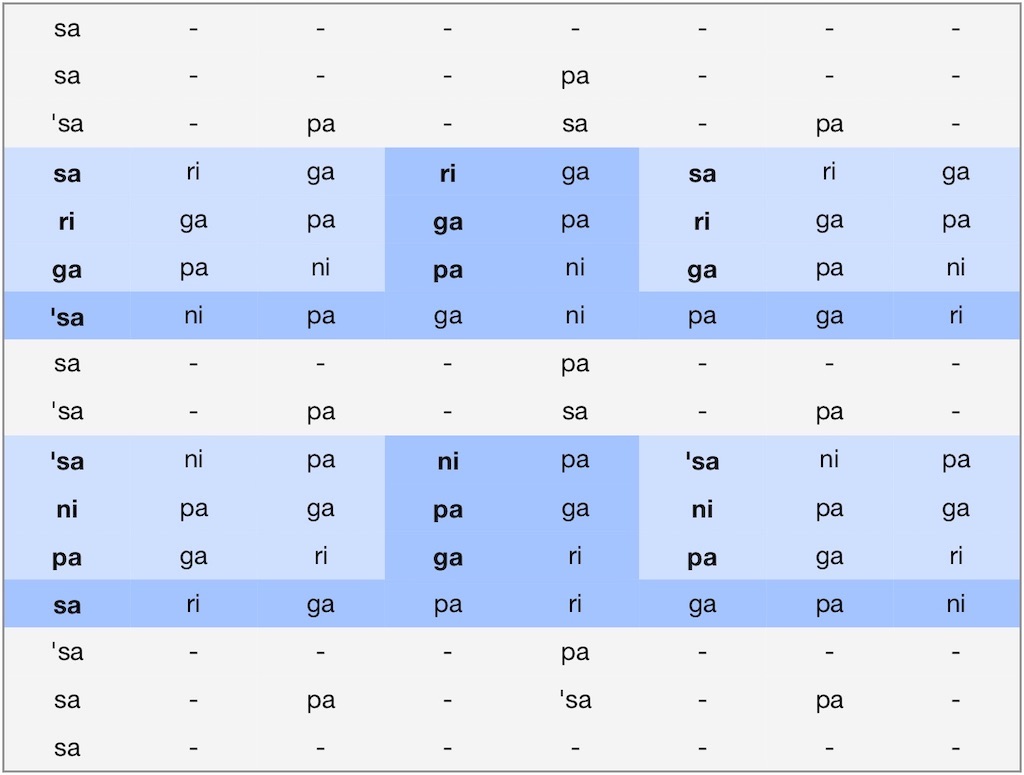

“Flow” exercises

A series of “Flow” exercises invites learners to practice all the 72 musical scales of Carnatic music (“mela” or mēlakarta rāga). It is meant to supplement the comprehensive standard syllabus (abhyāsa gānam) attributed to 16th c. composer Purandara Dasa.

Repeated practice need not be tedious; instead it instantly turns joyful whenever we remind ourselves that Indian music “is created only when life is attuned to a single tune and a single time beat. Music is born only where the strings of the heart are not out of tune.” – Mahatma Gandhi on his love for music >>

As regards “time beat” in Carnatic music, the key concept is known as kāla pramānam: the right tempo which, once chosen, remains even (until the piece is concluded). | Learn more >>

Music teachers will find it easy to create their own versions: exercises that make such practice more enjoyable. | Janta variations >>

Concept & images © Ludwig Pesch | Feel free to share in accordance with the

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike license >>

Become fluent with the help of svara syllables (solmisation): practice a series of exercises, each based on a set of melodic figures that lend themselves to frequent repetition (“getting into flow”) | Practice goal, choosing your vocal range & more tips >>

South Indian conventions (raga names & svara notation): karnATik.com | Guide >>

raagam: hamsadhvani

Aa: S R2 G3 P N3 S | Av: S N3 P G3 R2 S

Having but 5 notes (instead of 7), this type of raga pattern is traditionally classified as being “derived” (janya) from a melakarta raga. More specifically, text books refer to any raga limited to 5 notes as audava raga.

The above svara pattern may be sung, hummed or practiced silently with several svara variants you are already familiar with (e.g. raga Dhirasankarabharanam, mela 29, resulting in Carnatic raga Hamsadhvani which has long been popular among Hindustani musicians as “Hansadhvani”). For details on popular Hindustani ragas, refer to The Raga Guide by Joep Bor.

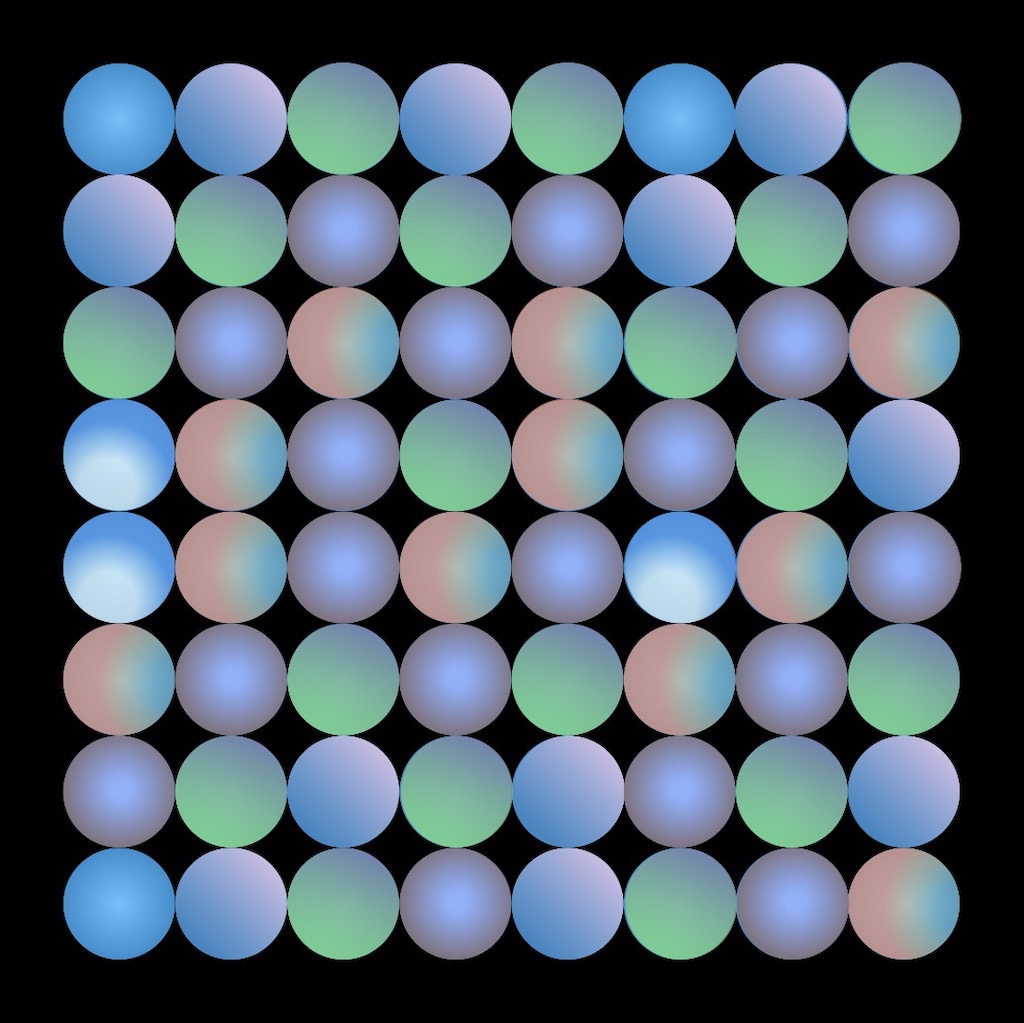

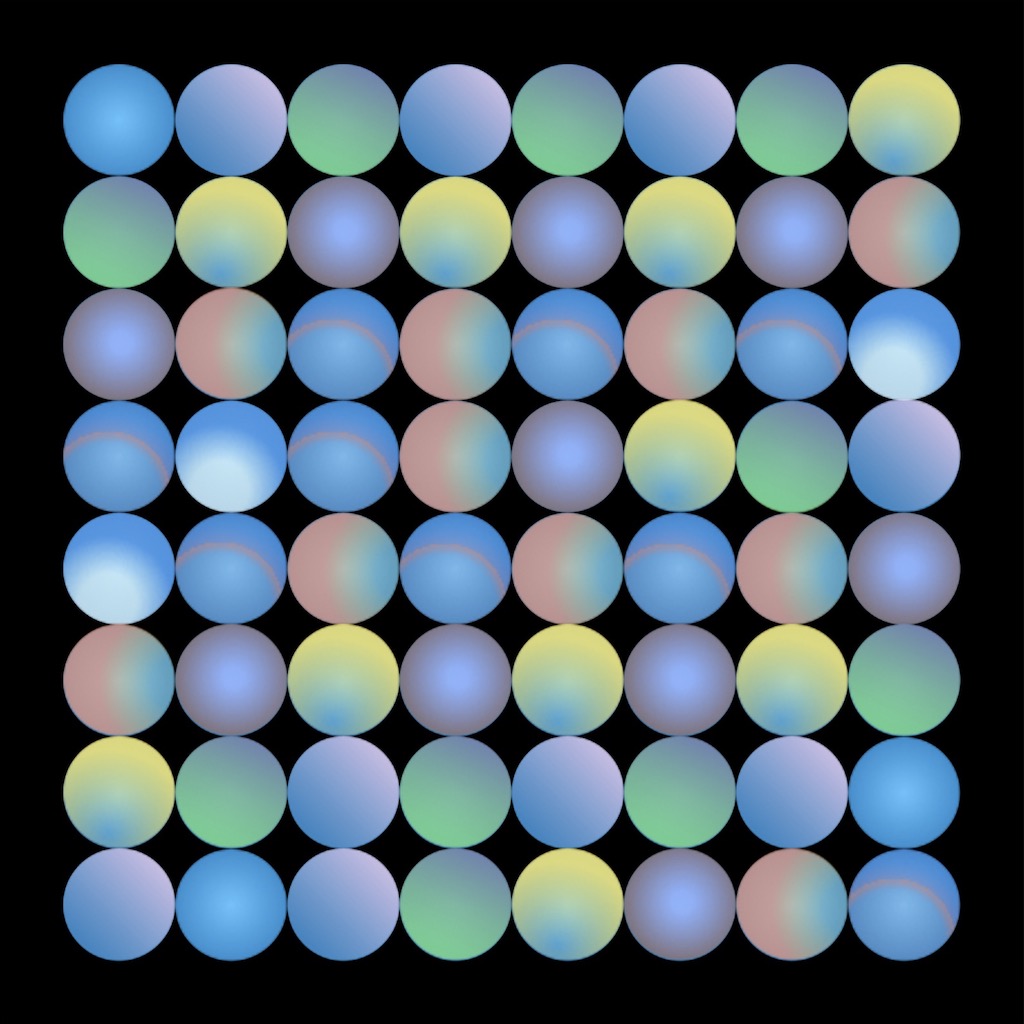

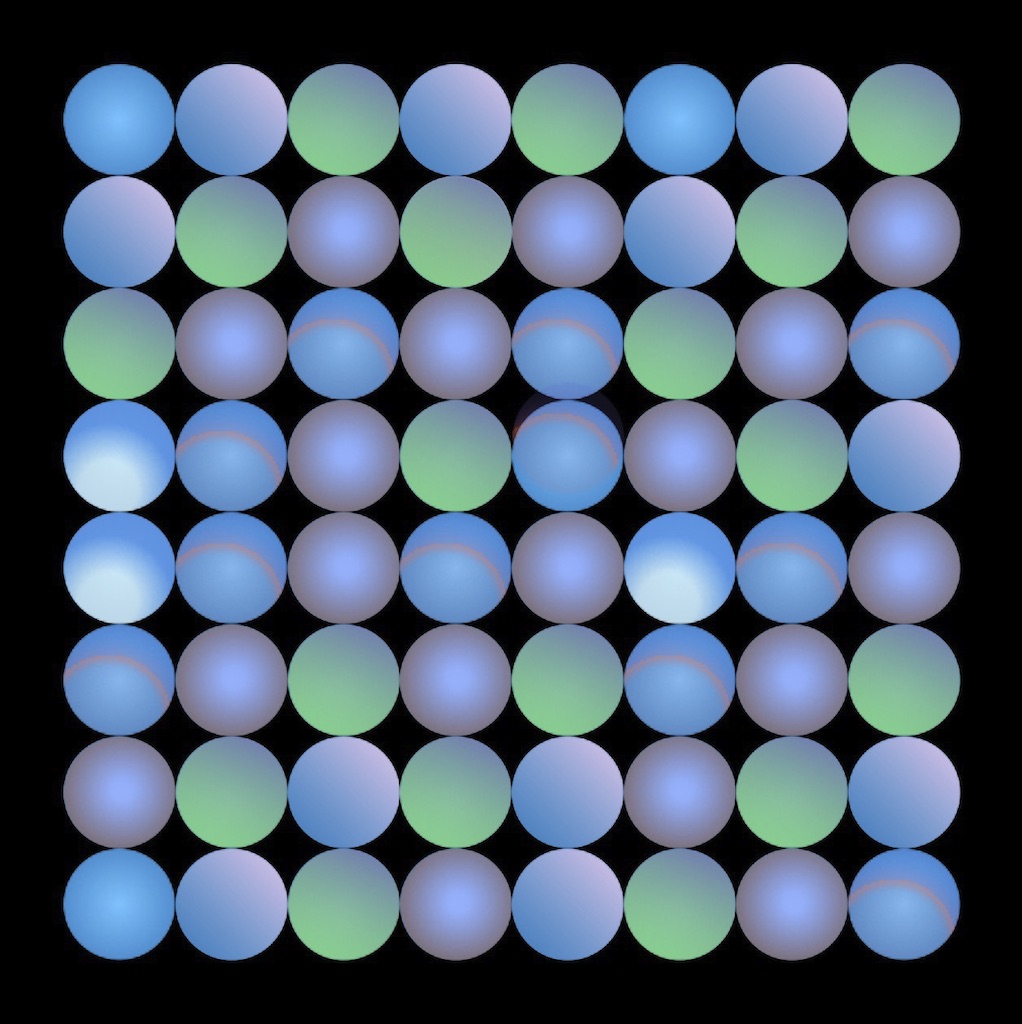

Once internalized you may want to contemplate and remember the same exercise with the help of the “8 x 8 beads” pattern shared here >>

Practice another raga with 5 notes here >>

Information about the persons, items or topics

- Find song lyrics

- Research & Custom search engines

- The Oxford Illustrated Companion to South Indian Classical Music

- Suppliers of books & musical instruments

Learn & practice more

- A brief introduction to Carnatic music (with music examples and interactive map)

- Free “flow” exercises on this website

- Glossary (PDF)

- Introduction (values in the light of modernity)

- Video | Keeping tala with hand gestures: Adi (8 beats) & Misra chapu (7 beats)

- Voice culture and singing

- Why Carnatic Music Matters More Than Ever

- Worldcat.org book and journal search (including Open Access)