Explore renditions of raga Vasanta on YouTube >>

Find song lyrics (composers) & translations for these and other ragas >>

Download this audio file (2 MB, 2 min. mono)

Credit: eSWAR / FS-3C Sruthi petti + Tanjore Tambura

Fondly invoking “spring” with ragas Vasanta & Basanta

A suggested by its name, Vasanta occupies a special place for evoking the moods and longings associated with “spring time”. It hardly surprises that its Bengali counterpart Basanta occupies pride of place among the songs composed by Rabindranath Tagore, a poet known for his fondness of Carnatic music (Reba Som). He felt that nature has been the prime inspiration for humankind from the very dawn of civilization and therefore remains relevant for modern society as well. According to him, this is all about happiness for all, not to be confused with craving for “respectability”:

“Ours is a society in which, through its tyrannical standard of respectability, all the members are goading each other to spoil themselves to the utmost limit of their capacity. […] True happiness is not at all expensive. It depends upon that natural spring of beauty and of life, harmony of relationship.“ – Rabindranath Tagore in “Robbery of the soil” (included in Poet And Plowman by Leonard Elmhirst (Visva-Bharati University, Calcutta 1975), pp. 34 & 36

In another context (his Foreword to S Radhakrishnan’s The Philosophy of Upanishads), he suggests the path of “sympathy and co-operation”; a simple one that provides orientation in a crisis-ridden world (then as today) while brightening the lives of countless readers on a daily basis:

“When our self is illuminated with the light of love, then the negative aspect of its separateness with others loses its finality, and then our relationship with others is no longer that of competition and conflict, but of sympathy and co-operation.”

So rather than looking backwards, his outlook seems all the more relevant for our times considering his deep concern for freedom and self-expression:

“Society as such has no ulterior purpose. It is an end in itself. It is a spontaneous self-expression of man as a social being. It is natural regulation of human relationships, so that men can develop ideals of life in cooperation with one another.” – Rabindranath Tagore quoted by Pulak Dutta in Santiniketan: Birth of Another Cultural Space (from The English Writings of Rabindranath Tagore, Vol. II, Sahitya Akademi, 2004, p. 421), p. 42

And such ideals, in Tagore’s view, are the very essence of being human:

“It is not the distinctive quality of man to be a mere repetition of his ancestors. Animals cling to the nests of their effete habits; man expresses himself age after age in new creations.” – Rabindranath Tagore in 1931 (Tagore on Gandhi), p. 31

For anyone yet unconvinced by Tagore’s profound yet simple message, let’s ponder another influential writer who happened to be born in India:

“If a man cannot enjoy the return of spring, why should he be happy in a labour-saving Utopia? … I think that by retaining one’s childhood love of such things as trees, fishes, butterflies and … toads, one makes a peaceful and decent future a little more probable, and that by preaching the doctrine that nothing is to be admired except steel and concrete, one merely makes it a little surer that human beings will have no outlet for their surplus energy except in hatred and leader worship.” – George Orwell quoted in Two Cheers for Democracy by E.M. Forster (London: Penguin Books 1976, p. 76)

If, on the other hand, our innate “surplus energy” is properly channelled through creativity, here is a path open to all of us:

“Of all living creatures in the world, man has his vital and mental energy vastly in excess of his need, which urges him to work in various lines of creation for its own sake […] The voice that is just enough can speak and cry to the extent needed for everyday use, but that which is abundant sings, and in it we find our joy. Art reveals man’s wealth of life, which seeks its freedom in forms of perfection which are an end in themselves. […] All that is inert and inanimate is limited to the bare fact of existence. Life is perpetually creative because it contains in itself that surplus which ever overflows the boundaries of the immediate time and space, restlessly pursuing its adventure of expression in the varied forms of self-realisation.” – Rabindranath Tagore in The Religion of an Artist

Or, in as convincingly argued by noted linguist Ganesh Devy in The Telegraph, “What unites Indians is a love for songs”.

Beyond India, this may well constitute our most widely shared cultural trait around the globe. So creating spaces for “varied forms of self-realisation” was a major cause Tagore espoused throughout his life. He inspired institution-building beyond his unique creation Santiniketan (“abode of peace”) as to empower future generations for the sake of a more just and peaceful world:

“It does not need a defeatist to feel deeply anxious about the future of millions who, with all their innate culture and their peaceful traditions are being simultaneously subjected to hunger, disease, exploitations foreign and indigenous, and the seething discontents of communalism.” – Amartya Sen quoting from a letter to Leonard Elmhirst, “the English philanthropist and social reformer who had worked closely with him on rural reconstruction in India (and who had gone on to found the Dartington Hall Trust in England and a progressive school at Dartington that explicitly invoked Rabindranath’s educational ideals)

Their ideals and joint efforts anticipated major goals included in the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights – to begin with, health and well-being including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services – and it is up to each of us to first realize our shared humanity:

“There lies before us, if we choose, continual progress in happiness, knowledge, and wisdom. Shall we, instead, choose death, because we cannot forget our quarrels? I appeal, as a human being to human beings: remember your humanity, and forget the rest. If you can do so, the way lies open to a new Paradise; if you cannot, nothing lies before you but universal death.” – Bertrand Russell quoted by Sarah Bakewell in Humanly Possible: Seven Hundred Years of Humanist Freethinking, Enquiry and Hope

Become fluent with the help of svara syllables (solmisation): practice a series of exercises, each based on a set of melodic figures that lend themselves to frequent repetition (“getting into flow”) | Practice goal, choosing your vocal range & more tips >>

South Indian conventions (raga names & svara notation): karnATik.com | Guide >>

raagam: vasantA 17 sUryakAntam janya

Aa: S M1 G3 M1 D2 N3 S | Av: S N3 D2 M1 G3 R1 S

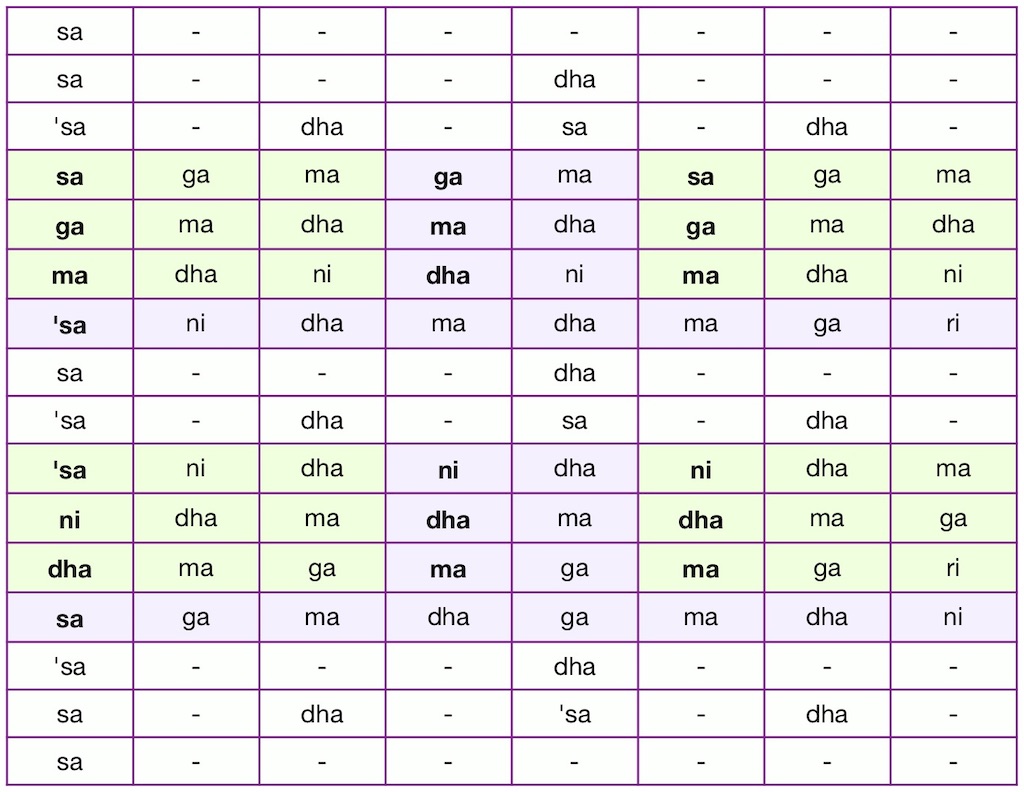

“Flow” exercises

A series of “Flow” exercises invites learners to practice all the 72 musical scales of Carnatic music (“mela” or mēlakarta rāga). It is meant to supplement the comprehensive standard syllabus (abhyāsa gānam) attributed to 16th c. composer Purandara Dasa.

Repeated practice need not be tedious; instead it instantly turns joyful whenever we remind ourselves that Indian music “is created only when life is attuned to a single tune and a single time beat. Music is born only where the strings of the heart are not out of tune.” – Mahatma Gandhi on his love for music >>

As regards “time beat” in Carnatic music, the key concept is known as kāla pramānam: the right tempo which, once chosen, remains even (until the piece is concluded). | Learn more >>

Music teachers will find it easy to create their own versions: exercises that make such practice more enjoyable. | Janta variations >>

Concept & images © Ludwig Pesch | Feel free to share in accordance with the

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike license >>

Tradition and change: integrity matters, even in the digital age!

In this course, new exercises are introduced with due respect for integrity – respect for a music that has evolved over several centuries (in its present concert format) and far beyond (as regards thought provoking concepts that kindle long-term immersion).

Some of the exercises and methods facilitate continuous or frequent practice among learners who struggle with multiple commitments.

So this is all about the kind of active involvement in a tradition wherein music is simply indispensable for leading a fulfilled life. This also explains why long-term commitment is compatible with socio-economic and scientific change. This calls for imagination, a fact reflected in text books that highlight the importance of manodharma sangita, a concept reaching beyond “improvisation” as understood in Western music.

We may therefore safely conclude that both commitments, learning and teaching, are by no means determined by an individual’s station in life.

For this reason, lessons may either be shared regularly and personally (by a guru, in the past largely informally within a household known as gurukulam), or without personal contact by emulating an inspiring exponent – alive or otherwise (manasa guru, manasika guru). Many musical biographers and hagiographers share a conviction that a learner’s choice for either approach – personal or indirect lessons – tells little if anything about an accomplished musician’s status.

In short, this is all about dedication and integrity, even in the digital age!

Listen to Uma Ramasubramaniam demonstrating the svaras (notes) for the present raga(s) on Raga Surabhi >>

Note: this recording has no fifth note “Pa”

(as advised for those janya ragas wherein “Pa” will not be sung or played)

Download this audio file (2 MB, 2 min. mono)

Credit: eSWAR / FS-3C Sruthi petti + Tanjore Tambura

Having but 6 notes (instead of 7), this type of raga pattern is traditionally classified as being “derived” (janya) from a melakarta raga. Text books refer to any raga limited to 6 notes as shadava raga. More specifically, raga Vasanta is an audava-shadava raga which means it has 5 notes in ascending, and 6 in descending melody patterns.

The most characteristic feature in the above svara pattern is the absence of the fifth note (pa) – the very note that conveys a sense of balance in most other ragas.

Up-to-date press coverage of person and topics

Periodicals and sites included | More resources | Disclaimer >>

Please note that the above figures lend themselves to several “Carnatic sister ragas”.

Learn more and download a free mela-pocket guide here: Boggle Your Mind with Mela (BYMM) method – free mini course >>