Backup: PDF-Repository >>

Full screen viewing and download link:

https://archive.org/details/voice-culture-and-singing-kalakshetra-quarterly-1983

Tips: 1. Search inside this file by first clicking on the (…) Ellipses icon; 2. click eBook title to access [ ] Toggle fullscreen; 3. to Read this book aloud, use the headphone icon.

Voice Culture and Singing by Friedrich Brueckner-Rueggeberg

Kalakshetra in 1983 © Ludwig Pesch

This course material was originally produced for – and used by – teachers and students at Kalakshetra College of Fine Arts, today known as Rukmini Devi College Of Fine Arts. To enjoy some of the vocal (Flow-) exercises offered for free on the present course site, it is useful to first identify a vocal range which suits your own voice (which may changes in the course in the day as well).

Tradition and change: integrity matters, even in the digital age!

In this course, new exercises are introduced with due respect for integrity – respect for a music that has evolved over several centuries (in its present concert format) and far beyond (as regards thought provoking concepts that kindle long-term immersion).

Some of the exercises and methods facilitate continuous or frequent practice among learners who struggle with multiple commitments.

So this is all about the kind of active involvement in a tradition wherein music is simply indispensable for leading a fulfilled life. This also explains why long-term commitment is compatible with socio-economic and scientific change. This calls for imagination, a fact reflected in text books that highlight the importance of manodharma sangita, a concept reaching beyond “improvisation” as understood in Western music.

We may therefore safely conclude that both commitments, learning and teaching, are by no means determined by an individual’s station in life.

For this reason, lessons may either be shared regularly and personally (by a guru, in the past largely informally within a household known as gurukulam), or without personal contact by emulating an inspiring exponent – alive or otherwise (manasa guru, manasika guru). Many musical biographers and hagiographers share a conviction that a learner’s choice for either approach – personal or indirect lessons – tells little if anything about an accomplished musician’s status.

In short, this is all about dedication and integrity, even in the digital age!

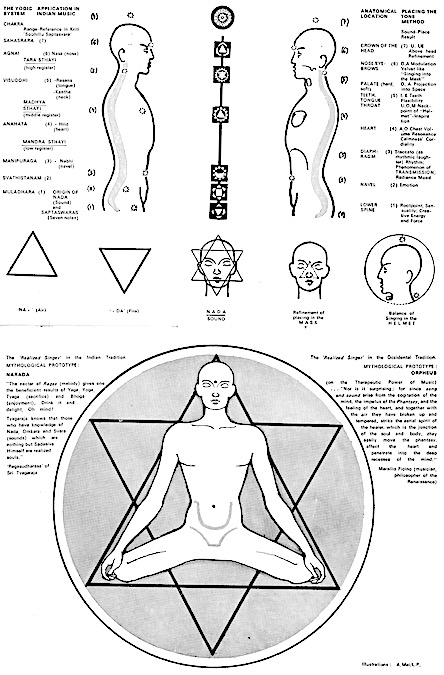

“The sage Bharata considered the voice an instrument in itself, calling it the sharira vina, or bodily lute. In that light, the similarities between the cakras and the Western anatomical scale are satisfyingly unifying, but they aren’t, if we think about it, surprising. Indian or European, we have, after all, the same instrument: the human body.” – Samanth Subramanian in Body and soul

Learn more

Browsing through a copy of the very new, extremely handsome, second edition of The Oxford Illustrated Companion to South Indian Classical Music, compiled by Ludwig Pesch, I came upon an intriguing diagram. In a chapter titled “The Voice in South Indian Music”, there is a line sketch of two furrow-browed men, each a mirror image of the other. Under the left-hand man is the caption: “Cakra concept—Indian voice culture and its centres of energy”; under his counterpart: “Placing the tone—Western voice culture based on anatomy”.

The two voice cultures developed independently, but the illustration points to keen similarities. In the West, the lower registers of the scale are thought to emerge from the area around the lower spine, where the attendant qualities of energy and sensuality reside. The scale then moves up the body, passing the heart (calmness, cordiality) and mouth (projection, flexibility), ending with its upper registers hovering around the crown of the head.

This anatomical scale, Pesch says, is often used by opera singers and those who sing the romantic song-cycles known as Lieder, and they associate specific spots in the anatomy with specific notes. For example, the resonating chamber of the human chest produces the vowels “a” and “o”, while the throat produces the vowel “u” and the consonant “m”.

The Indian system of voice, on the other hand, is based on the system of cakras (or chakras), centres of energy that run up and down the longitude of the human body. At the base of the spine is the muladhara cakra which, according to Pesch, is “thought of as the source of primordial sound”. In one lyric of his song Shobillu Saptaswara, the composer Thyagaraja strung together these bodily origins of the musical notes. “Naabhi hrut kantha rasana naasaadhula yandu,” he sings—the notes “glow in the navel, the heart, the neck, the tongue and the nose of the human body”. These are, Pesch says, “more than poetic images if understood in the light of other traditions of voice culture”.

A couple of years ago, a music teacher introduced me to this concept, and she urged me to try it for myself by paying attention to the physicality of my slow ascent up the scale. She started me off half an octave below the base note of “Sa”, which had to be dredged from the pit of my belly. I sensed the note of “Sa” itself reverberating around my chest, and one octave higher, the upper “Sa” felt like it was trying to escape through the bridge of my nose. Three or four notes higher, and sure enough there was a fizzing around the edges of my scalp (that was as high as I could go; beyond that, it was all supersonic).

The sage Bharata considered the voice an instrument in itself, calling it the sharira vina, or bodily lute. In that light, the similarities between the cakras and the Western anatomical scale are satisfyingly unifying, but they aren’t, if we think about it, surprising. Indian or European, we have, after all, the same instrument: the human body.

Source: Raagtime by Samanth Subramanian in Body and soul, Livemint, 13 March 2009

URL: https://www.livemint.com/Leisure/jws2RmIuMprzTCiGzDldnN/Body-and-soul.html

Date Visited: 12 July 2025

Beyond the lyrics that naturally call for specific moods or feelings (bhava) to be expressed, practical exercises for beginners and advanced learners1 may be compared with western solfège; in our context for the purpose of articulating, appreciating, memorizing or communicating Carnatic raga phrases in characteristic ways (with or without conventional notation); eventually to be combined with rhythmic figures as part of compositions or improvisations in virtually any part of a concert.

Meaningless and uncontrolled singing and exercising are rather harmful since the long-term memory of the brain needs to be supplied with correct impulses which requires immediate recognition of functional disorders and their correction.

Herein lies the great and far-reaching responsibility of the teacher whose full care and control is demanded in order to allow the singer to acquire an automatic and playful sense for the correct usage of his voice. In this manner, he is relieved sufficiently to devote himself fully to content and presentation of his music (described as Bhava in India). […]

Many victims of either wrong techniques of singing or careless teachers keep wandering from teacher to teacher in pursuit of their shattered hopes. This fact lends weight to the concept of voice control from the very beginning before defects can encroach that are so hard to correct later on, if at all.

Quote from page 15 in the printversion | Learn more >>

Context

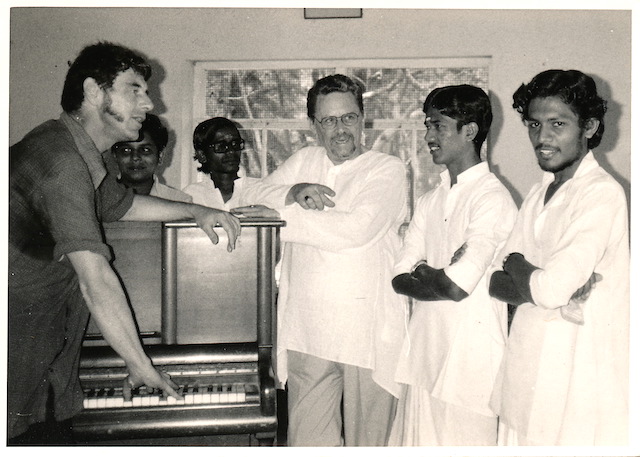

A two week long voice culture course was offered at the request of its Founder-Director, Rukmini Devi (1904-1986) when introduced to the renowned singer and voice trainer, Friedrich Brueckner-Rueggeberg in 1982.

This project was conceived on the basis of earlier experiences, namely that Indian singers would benefit from time-proven as well as modern methods such as described here, mainly in order to prevent injury caused by mechanical practice (e.g. a lack of awareness that a pupil’s vocal range, breathing and posture should be taken into account).

The method described here is oriented towards “intercultural learning” which explains why it has since been adopted by several voice coaches from all over India, be it for “classical” singing or otherwise.

It has also been adapted for a major chapter on vocal music in The Oxford Illustrated Companion To South Indian Classical Music by Ludwig Pesch (Oxford University Press, in print since 1999, 2nd rev. ed. 2009).

Credits

The Chennai branch of the Goethe Institut (German cultural institute, better known as Max Mueller Bhavan) sponsored Friedrich Brueckner-Rueggeberg and his senior disciple Peter Calatin to conduct the voice training course hosted by Kalakshetra in 1983 for which the present contents was created.

First published by K. Sankara Menon and edited by Shakuntala Ramani in Kalakshetra Quarterly Vol. V, No. 3 (Chennai, 1983).

Co-author, translator and researcher (adaptation to the Indian context including illustration and photography): Ludwig Pesch – the author’s former student at Freiburg Musikhochschule (Germany) – then a student of Kalakshetra College.

Illustration (graphics): Alain Mai

- As pointed out by Gouri Dange, learners are well advised to approach their daily practice with the same respect that characterizes the renditions of a revered musician:

“Every kind of music has a protocol for ‘beginners’ or ‘learners’. Students must practise paltay, alankaras, scales, études, tonalisation exercises, depending on the kind of music they pursue. […] It is surely a disservice to a raga and to those who lift it to its best potential, and even more so a disservice to the young student, to allow the mental stamping of some ragas as ‘learner material’.” [↩]