Courtesy ©

The Sruti Foundation

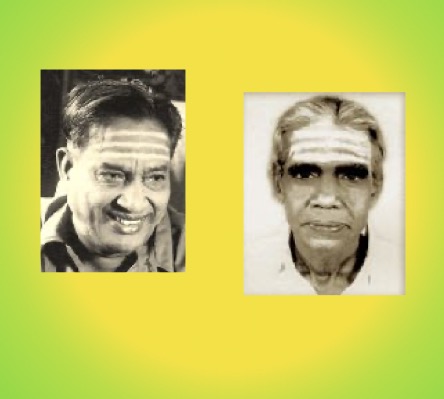

Many years in the making, the present monograph is a tribute to two great musicians, fondly remembered by their heirs and audiences just as the many experts consulted by its author, Dr. Pia Srinivasan (1931-2022). She remained steadfast in her commitment even if their rare insights had to be shared posthumously.

For her and her husband, Prof. S.A. Srinivasan (1932-2019), a ragamalika or “melodious garland” carried fond memories of auspicious occasions: the festive mood and fragrance when an eminent person is garlanded with fresh flowers as a sign of respect.

Ludwig Pesch (ed.), Amsterdam 2025

Learn more

From time immemorial, flower garlands have been offered to musicians, composers, dancers and teachers, be it after a performance or during festivals like the popular Tyagaraja Aradhana celebrations. The preciousness associated with either “type” of garland – fragrant or melodic – justifies the extraordinary care and skill invested in its creation.

Such connotations come to mind when considering the limitations posed by Western staff notation as regards Indian music where melodic intricacies are committed to memory and performed without reference to written records. In the present monograph just a few musical signs and symbols serve to compare a particular phrase or motif rendered on one occasion with similar renditions heard on other occasions. This clearly differs from the way Western composers have traditionally used notation to indicate how their creations should be sung or played. Conversely, prescribing more details than needed would hinder rather than advance artistic creation from an Indian perspective – comparable to prescribing each and every feature of a flower garland as if it were a mere consumer product rather than a carefully crafted expression of respect, gratitude and devotion (bhakti).

In other words, discerning audiences expect to witness a modicum of spontaneity even in a “classical” Carnatic recital; and this irrespective of a performer’s status. So if Indian musicians as well as music teachers have come to prefer a “stenographic” notation system – one that serves them well as an aid to memory – this reflects their pragmatic (rather than conservative) approach to learning as put by Prof. S.R. Janakiraman: “much more has to be left to the musician [as] it is futile to put all music on paper.” (A remark noteworthy for being “the last word” in his Essentials of Musicology in South Indian Music; Chennai: The Indian Music Publishing House, 2008)

The English text follows conventions proposed by S.A. Srinivasan, without whom this publication would have been inconceivable. Their shared love of “Carnatic” or “classical South Indian music” prompted both him and his wife Pia to discretely support Carnatic musicians and teachers in need, including some who advanced of India’s cultural and social diversity. It is worth mentioning here that their observations on social norms had earlier prompted them to author The Goddess Mariyamman in Music and in Sociology of Religion (https://archive.org/details/mariyamman-in-music, open access). This monograph was preceded by liner notes for the award winning recording titled “Vina music from South India” (https://en.schott-music.com/shop/sambho-mahadeva-no174008.html) which elucidates the sophisticated Karaikudi tradition for the benefit of newcomers and connoisseurs (rasika) alike.

The above glimpses of “two musical lives well lived” would remain incomplete without mentioning their love of nature, evident from Pia’s 1968 diary entry which may be paraphrased as follows:

During our stay in the Nilgiri hills we woke up to the staccato tune of a small bird locally known as Manikkuruvi – a “bird treasured like a jewel” for singing precise motifs capable of evoking certain ragas in listeners’ minds:

“Da alcuni giorni la mattina presto sentiamo un uccellino che canta con un buono staccato. […] Ho racontato al maestro di canto dell’uccellino che ci svegliava la mattina in montagna con una melodia ben precisa; in quella zona – ci ha detto – ci sono uccelli ‘musicali’, che cantano cioè secondo certi raga, si chiamano manikkuruvi: ‘uccello’ (kuruvi, è onomatopeico) ‘prezioso come un gioiello’ (mani).” – Il raga che porta la pioggia, pp. 60, 102

In short, their joint endeavours never took anything or anyone for granted and, instead, convey a sense of wonder and dignity in every way imaginable without becoming sentimental. This combined interest naturally calls for critical inquiry, not idealization. It prompted S.A. Srinivasan to pursue yet another life project worth mentioning here: a monograph titled Nonviolence and holistically environmental ethics gropings while reading Samayadivākaravāman̲amun̲i on Nīlakēci (https://worldcat.org/en/title/929910155).

Full text & Audio

Text & music: Tanjore Sankara Iyer (mp3, 6 MB, duration 6:03)

Timings, incl. cittai svaras and pallavi refrain at the end

pallavi: 0:01→1:21

carana 1: 1:22→3:01

carana 2: 3:02→4:12

carana 3: 4:13→6:03

Text: Appar

Music: D.K. Jayaraman (mp3, 15,6 MB, duration 16:19)

Timings

raga 1: Kalyani: 0’01″→5’13”

(vocalises upon the text: 2’25″→2’58” / violin solo: 3’01″→5’13”)

raga 2: Kharaharapriya: 5’15″→10’38″

(vocalises upon the text: 7’25″→8’20” / violin solo: 8’21″→10’38”)

raga 3: Saveri: 10’40″→13’25″

(vocalises upon the text: 12’41″→13’25”)

raga 4: Madhyamavati:13’26″→16’17”

(vocalises upon the text: 15’24″→16’17”)