While “democratic values” would seem an anachronism in the context of the hierarchical society wherein its inventor flourished, we are free to envisage new possibilities inherent in the melakarta scheme as such:

The research in the field of pure musicology yields some interesting theoretical results, useful from technical and historical points of view. Venkatamakhi while justifying the derivation of 72 melakartas by permutation and combination interestingly remarks that countries are many with people having variety of tastes and it is to please them ragas have been invented by musicians. Some are already known while some are in the process of being brought to life, while some may be invented in future, while those surviving only in treatises and the ragas not known at all during their time may be brought to life in future, for the benefit of the people.

Dr. S. Seetha in Tanjore as a Seat of Music (During the 17th, 18th and the 19th Centuries) (University of Madras 1981), pp. 433-4 [Download Link]

So appreciating and practicing Carnatic music is worth the effort not just for the sheer joy of it: there is unlimited scope for growth, like benefitting people irrespective of their cultural background or status in modern, democratic societies – even if this potential seems far from having been realized … until now!

Towards a broader conceptualization of Venkatamakhi’s vision

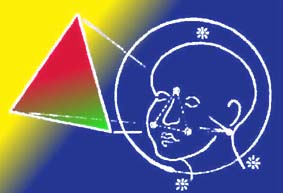

Let’s, for a moment, ignore the tabular arrangement of the 72 melakarta ragas and instead, regard each of the 12 cakra-s as a “range” or “district” (see sanskritdictionary.com). As a result, the melakarta system would lead us to the very realm wherein people having variety of tastes are free to explore new melodies. This would naturally involve fellow musicians from widely different cultural and social backgrounds connected – even related to one another – thanks to melodic features that merit closer attention.

As regards the raga-based music that underpins dramatic representation today (“classical” as well as “regional” dance and drama), the preference for some combinations of notes appears to follow a tendency widely shared across cultural boundaries, outlined as follows by Dale Purves:

“Musicians and listeners must have been aware long before the abstract conception of scales came into use that different tone collections tend to elicit different emotions” which entailed particular restrictions presumably serving “to maintain a mood of subdued reverence that differed from popular (‘folk’) music that then, as now, elicits more carnal emotions pertinent to the needs, desires, and disappointments of daily life”. – Music as Biology: The Tones We like and Why (Harvard University Press 2017), pp. 79-80

Dictionary search for truly curious minded learners

To understand the meaning and context of specific terms, use this search window:

Technical support for browser viewing

When a web browser fails to display a Google SafeSearch window, try the following:

click the current post heading (works when viewing a list of summaries)

directly view the websites include (e.g. Dictionaries)

More tips >>

Some clarifications on caste-related issues by reputed scholars >>