Image © Kutcherbuzz.com

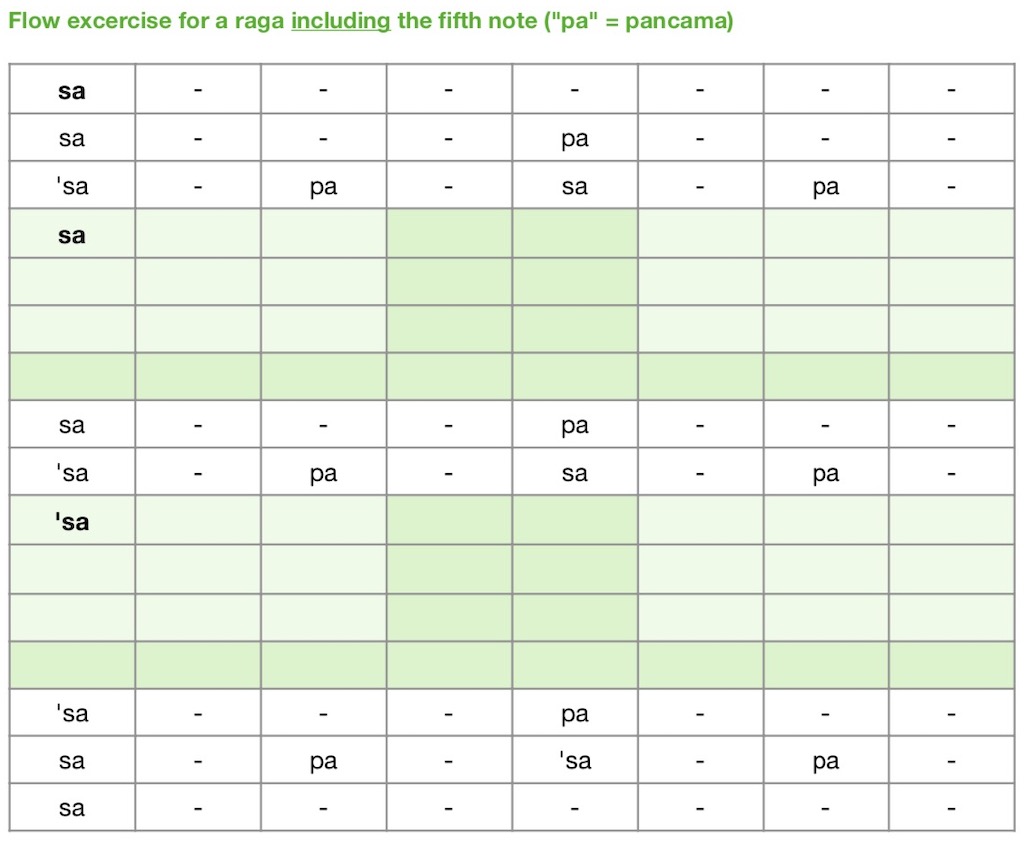

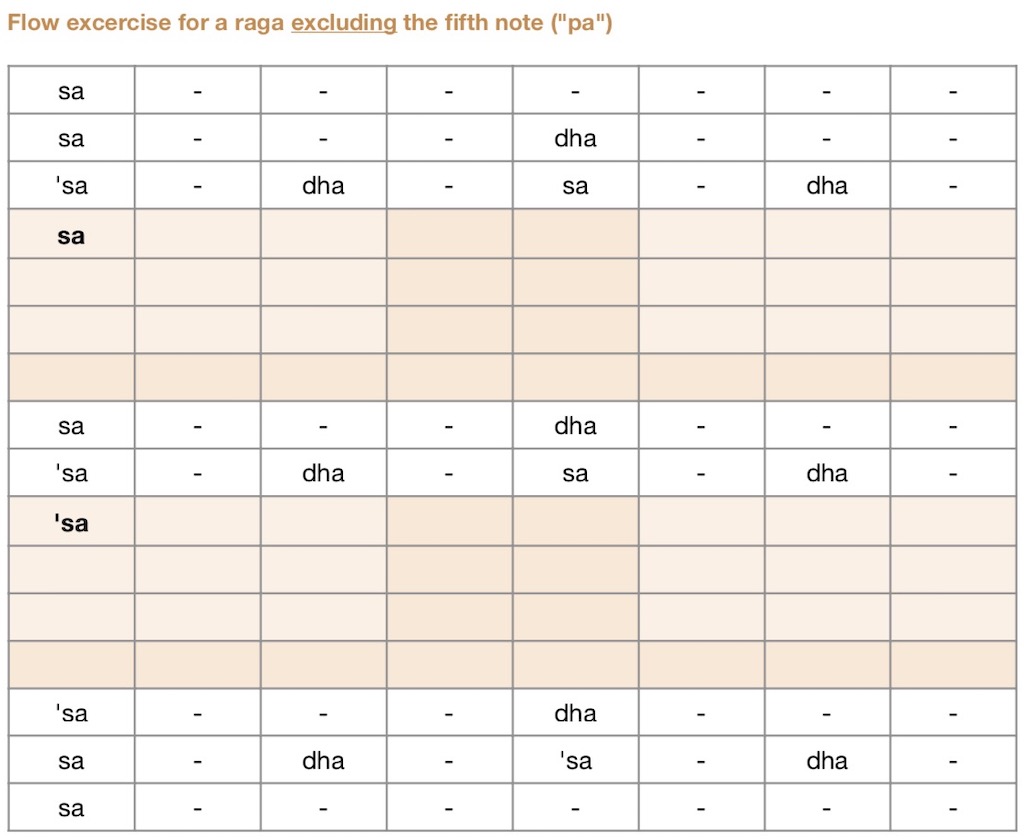

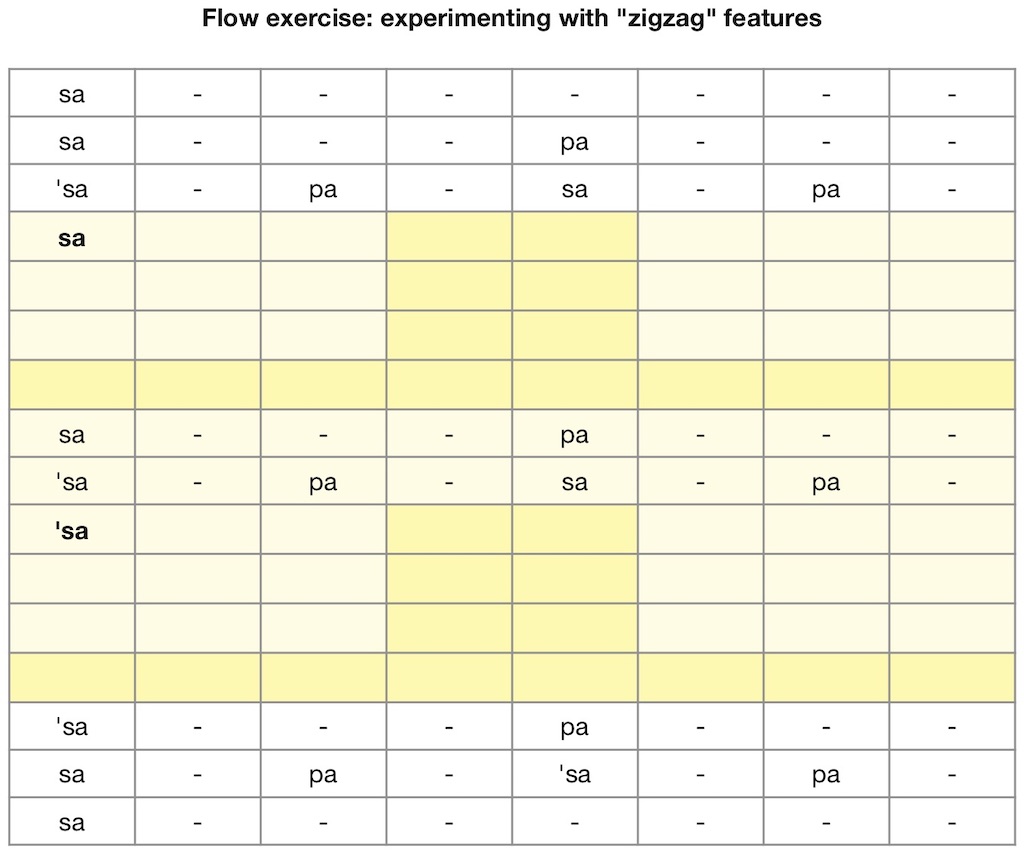

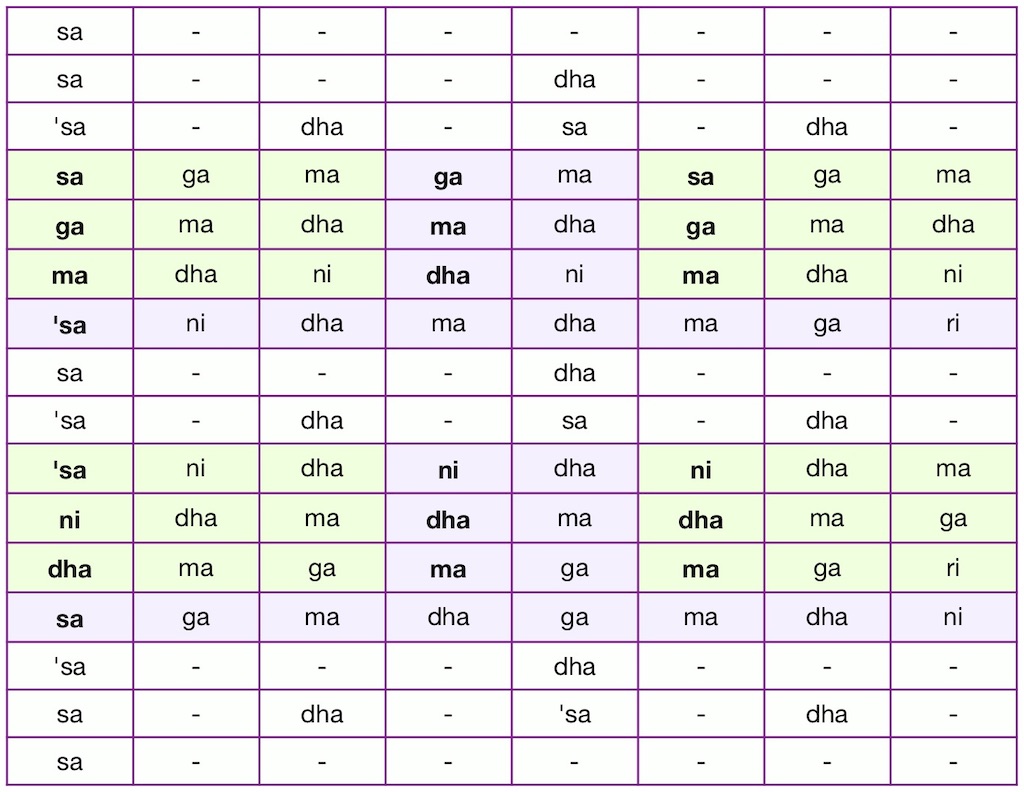

If there is a single feature of Carnatic music to account for its mesmerizing effect on listeners it may well be a feature known as kalapramanam: practicing rhythm (laya)1 and performing in the the “right tempo”2 (kālapramānam) which, once chosen, remains even or standardized.

Adopting it as part of regular practice enables musicians to perform in perfect alignment. Of equal importance are a number of benefits, including

- the possibility to actively involve discerning listeners (rasika) by “keeping tala” throughout a classical South Indian concert (using finger counts and hand gestures), thereby

- creating opportunities for music and dance students to imbibe the essence of rhythm (laya) right from the outset of their course

- practicing with scope for self-expression and adaptation (getting into the flow as part of “lifelong learning”)

- the unifying quality that sets Carnatic music apart beyond social and linguistic divides

The last point may be seen as test of the assertion made by the most beloved composer of South India: Sri Tyagaraja posing the rhetorical question: “Can there be any higher bliss than transcending all thoughts of body and the world, dancing with abandon?” – Intakannaanandam (learn more on karnATik.com), Bilahari raga, Rupaka tala

For details, also refer to the Oxford Illustrated Companion to South Indian Classical Music

- Glossary-cum-index

- In the following section(s)

- ‘”The sense of rhythm gives us a feeling of freedom, luxury, and expanse. It gives us a feeling of achievement in molding or creating. It gives us a feeling of rounding out a design… As, when the eye scans the delicate tracery in a repeated pattern near the base of the cathedral and then sweeps upward and delineates the harmonious design continued in measures gradually tapering off into the towering spire, all one unit of beauty expressing the will and imagination of the architect, so in music, when the ear grasps the intricate rhythms of beautiful music and follows it from the groundwork up through the delicate tracery into towering climaxes in clustered pinnacles of rhythmic tone figures, we feel as though we did this all because we wished to, because we craved it, because we were free to do it, because we were able to do it.” – Carl Seashore in Psychology of Music (New York: Dover Publications 1938/1967 quoted in Cosmic order, cosmic play: an Indian approach to rhythmic diversity by Ludwig Pesch [↩]

- “Carnatic music has this unique aspect where the musicians on stage and the audience explicitly put the tala on their hands. Each song has a particular tala and the related facets of rhythm include the tempo or kalapramanam of the song, the specifics of the tala — whether it is one of the Chapu talas or Suladi Sapta talas and its associated components, eduppu — the pivotal point where the melody starts in the tala cycle and this can occur at samam (the same starting point), before or after the tala commences [and] ‘kaarvai’ — versatile, rhythmic pause that is woven into the song itself or improvisations (kalpana svaras, korvais, pallavis). Another critical element is the arudi which can be described as a ‘landing point’ or the point of emphasis of a syllable of the lyric. The arudi is particularly important in the pallavi (part of Ragam Tanam Pallavi).” – Learn more: Arudi — the emphatic, landing point by KavyaVriksha, a “life long student of Music” [↩]

by

by